Originally published in Rewidling Britain Magazine on 3 Nov 2015

Or, as Oxford academic Paul Jepson puts it, nature conservation badly needs an upgrade. Here he presents the case for experimental rewilding

Originally posted to Rewilding Britain 03 Nov 2015

In the 1700s, Lord Cobham’s experimental landscape garden at Stowe blew the mind of cultured society and has set tastes in nature ever since. It initiated a transformation in cultured attitudes to nature – from one of abhorrence and indifference to aesthetic appreciation and intellectual curiosity.

‘Much like the terms ‘punk’ or ‘hippy’, rewilding is coming to signify an unsettling – a desire to shake up the present and shape futures.

I believe we should be taking inspiration from Stowe and creating public experiments in nature restoration that will unsettle and inspire; experiments that will interact with 20th century conservations practices to create new and re-invigorated forms of conservation fit for 21st century changes and challenges.

Our conservation institutions – and the ideas of what is natural, the framing of problems, and associated science, regulations, standards and professional practices – took shape in the wake of the cultural shock of environmentalism in the 1970s. They are ageing. Science and society has moved on.

Nature has become institutionalized. We are coming to associate nature conservation more with NGO brands such as the RSPB and WWF than with vibrant natural areas. We are beginning to treat our UK nature like a Grannie. A cherished, interesting and insightful Grannie who we enjoy being with, but a Grannie who is ailing and not the force she once was.

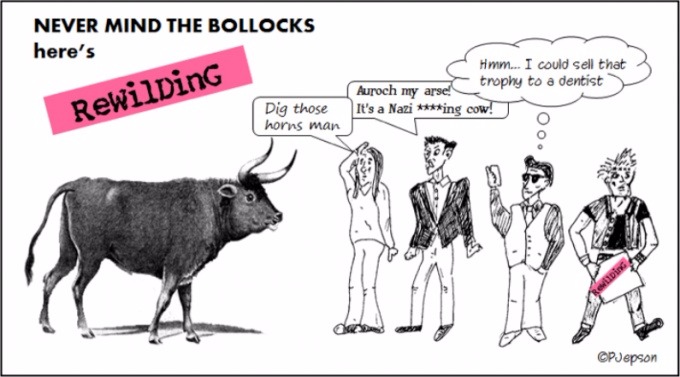

Rewilding is active, controversial and happening. Much like the terms ‘punk’ or ‘hippy’ it is coming to signify an unsettling – a desire to shake-up the present and shape futures.

It is an emerging movement responding to trends in ecology, conservation and society. Prominent among these are:

- The rise of functional ecology, which seeks to understand how the traits of species interact to produce functioning ecosystems. This is exposing the degree to which we have come to accept degraded ecosystems, and is changing conservation thinking from a focus on composition (units of nature in place) to function (relations between traits in context).A ‘resetting’ of expectations in conservation, which has come about in part due to the recovery of carnivore populations across continental Europe, and in part due the Dutch rewilding experiment at the Oostvaarderplassen (started in 1986) and compelling visions such as the ‘Pleistocene Park’ in Russia.Public demand for more exciting engagements with nature. George Monbiot captured this beautifully in the opening chapters of Feral, but it is visible for all to see in trends in outdoor recreation. Birders such as me are beginning to look dowdy in today’s countryside. It’s all mountain bikes, wild swimming, coasteering and digital-photography nowadays.

‘Experimental rewilding reserves would represent an edgy addition to our portfolio of landscape designations’

Not quite anarchy in the UK

Nature conservation needs an up-grade not a revolution. We don’t want to kill off Grannie and rip up all the advances of the last 40 years. However, we do need to move on and explore promising new avenues.

Rewilding represents a modernising force. The question is how do we proceed? What is the range of approaches that could be taken, and in what contexts and for what purposes would they be appropriate?

People and institutions are rightly resistant to change, but society loves experiments. Just as the Shard adds a funky talking point to the London sky-line, experimental rewilding reserves would, I believe, represent an edgy addition to our portfolio of landscape designations (from SSSIs to AONBs). Their purpose would be to create a radical ‘other’ which would position current conservation practice and thereby open up democratic discussion on the future of nature and conservation.

Experimental rewilding reserves are needed in order to develop a new applied inter-disciplinary conservation science. As yet, we don’t know much about techniques for ‘re-setting’ ecosystems, the dynamics this will create, at what scales it can be done and what limits society will put on all this.

Keep up to date with rewilding news and events Sign up to the Rewilding Britain newsletter

Existing rewilding projects are constrained by a raft of other legislation, from biohazard to health & safety. We need contained experiments where regulations can be relaxed and new approaches explored. The impact of such reserves would be enhanced if they are developed on low-conservation-value land within easy reach of urban areas, and if citizens, enterprise and local government are actively involved in their design and review.

I believe the land for experimental rewilding can be found. For example 800 ha of coal-mining landscapes have been put aside for conservation outside Leeds, and the national forest consultation (1987-1992) led to several bids from local authorities. A scheme that invites others to bid to be part of an experimental rewilding network is likely to produce innovative partnerships and ideas for putting rewilding into practice.

Rewilding visions are settling on five principles that could guide the design of experimental reserves.

1. A focus on restoring tropic levels and ecosystem processes. In practice this involves reassembling lost guilds of animals and seeing what emerges from ‘re-animated’ nature. There are indications from the Knepp Estate that nightingale recovery might be an ‘emergent property’ of a free ranging mix of cattle, horse and pig breeds and deer.

2. Relaxing wild/domestic, non-native/native binaries. Or, put another way, it doesn’t matter where something comes from [native/non-native], what matters is the role it can play [in restoring ecosystem function]. An example would be a reserve that experimented with the assembly of a large-herbivore guilds involving a mix of de-domestication cattle and horses (to replace the extinct auroch and tarpan) native deer and feral muntjac.

3. ‘Hands-in-pocket’ management: the idea that humans should step back and let ecological dynamics shape the habitats in the reserve. This will mean reserves that change from year to year and ‘boom & bust’ cycles for some species that could potentially ‘pump’ dispersal across regions.

4. Taking inspiration from the past but not replicating it. For me rewilding is about creating future natural heritage, new natures that evoke the past, but that can shape the future.

5. Rewilding the self. The idea of experimenting with spaces where people, if they so wish, can re-experience (within sensible limits) the sense of aliveness that comes with learning how to move safely within mega-fauna, has a lot of appeal for me.

In conclusion

Rewilding has entered the popular and scientific imagination. Now it is time to talk strategy and action. Because rewilding embodies a radical new conservation paradigm, a phase of pubic experimentation seems a realistic, sensible and exciting way forward.

About the author

Dr Paul Jepson is course director MSc Biodiversity, Conservation and Management at the University of Oxford. He transferred to academia from a successful career in conservation policy and management.