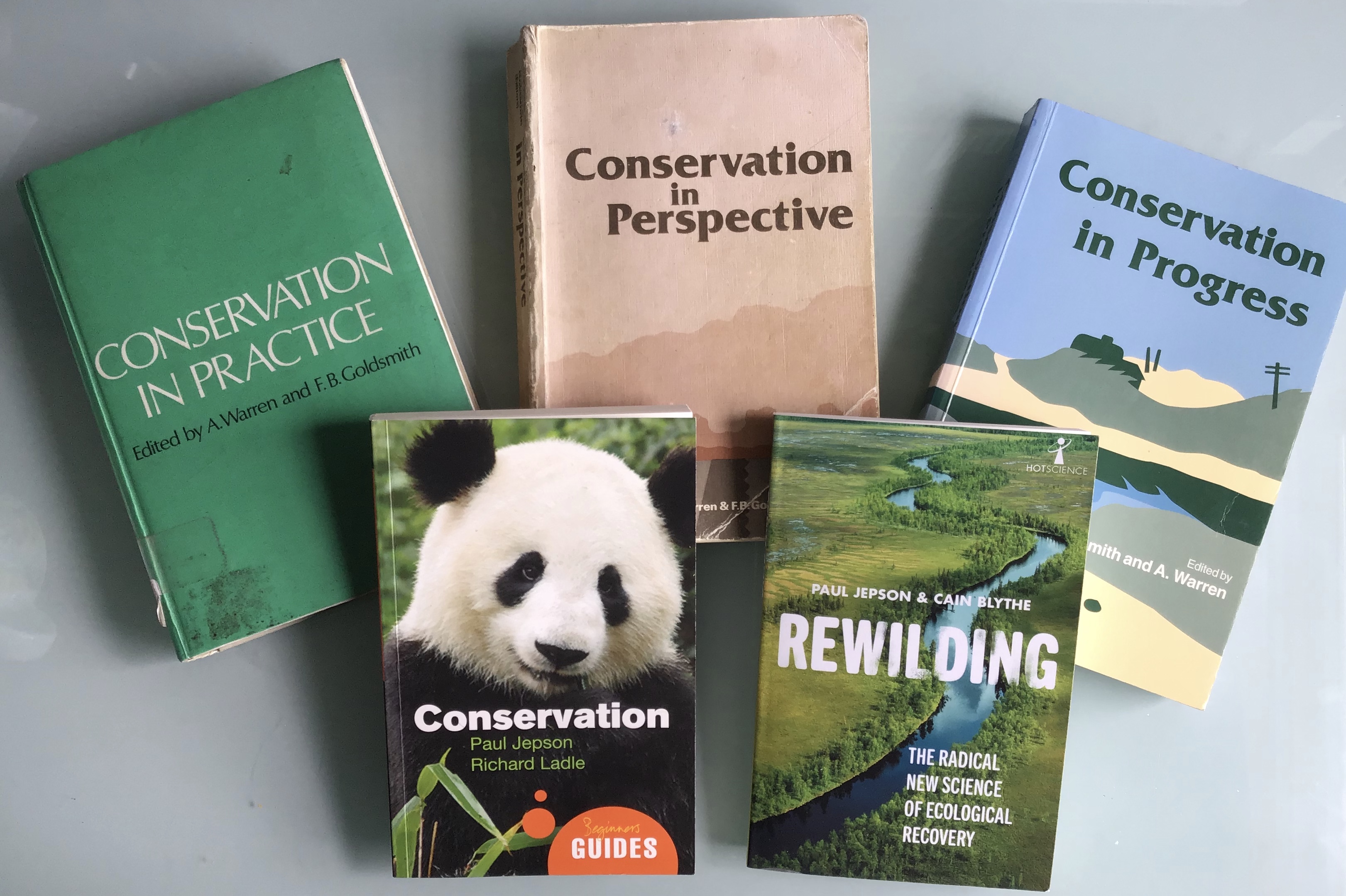

The print edition of my new book on rewilding arrived last week and, looking for a place for it in my bookcase, I realised that I placed my last book next to three classic volumes edited by Andrew Warren and Frank Goldsmith.

These volumes, printed in 1974, 1983 and 1993 contain collections of essays from scientists and policy makers who contributed to UCL’s MSc in Conservation, which was initiated by Max Nicholson first director of the Nature Conservancy (now Natural England.)

They were intended as a textbook-style resource for students on the UCL course but also a resource of latest thinking for professional conservationists working in government and NGOs. They contain some classic – now historical essays – on the concepts, science and policy of (mostly) UK conservation. These volumes enabled established conservation professionals to understand what aspiring conservationists were studying and promoted a receptiveness to, and maybe a desire for, their new knowledge.

A decade ago, my friend Richard Ladle and I perceived a widening gap between the theory and science taught on the MSc we were leading and the science and worldviews that are embedded within the practices and business models of many conservation employers. We explored the opportunity to produce a new ‘Warren and Goldsmith’ linked to Oxford’s MSc in Biodiversity. Conservation and Management. However, we soon realised that academic publishing incentives and workloads have moved on and it would be difficult to get something off the ground. Instead, and in the spirit of widening access to the curriculum of our MSc, we wrote a readable overview of the concepts, science and topics taught.

My new book on rewilding seeks to do the same. It covers the exciting and emerging multi-disciplinary science of rewilding which I had the privilege of curating and contributing to when I was Director of the MSc course. However, these books are published as part of series (Beginners Guides, Hot Science) and I am not sure they have the kudos and profile needed to fulfil the same ‘inter-generational professional knowledge flow’ role.

I see rapid change in the science underpinning conservation and how new developments are exciting, challenging and inspiring the younger generation. But I also recognise that many in senior conservation management positions were educated in the science of the 1990s or before and may be unfamiliar with the new science and/or worried that it may unsettle established practice.

Is this really an issue? Is there really a widening generation gap in the science of conservation and, if so, should we be thinking about ways to address it?

I am keen to hear the views of others on this theme.