On 19 April Rewilding Europe celebrated its 5th anniversary with a special gathering in Amsterdam called Wild Ways. The event included dialogue, a ‘rewilding’ market, previews of film projects, music by Lex Empress and two talks, one by Rewilding Europe MD Frans Schepers and one by myself. Here is the text of my talk.

Good evening Ladies and Gentlemen.

It’s a pleasure and a privilege to be here this evening.

I would like to offer some reflections on this question ‘Rewilding: why now?” and from two perspectives.

Firstly, Why are we celebrating the 5th anniversary of Rewilding Europe on this April evening in 2017, why not 1997 or 2007 or 2037? What forces have brought us together now?

Secondly, why does the 21st conservation movement need rewilding now?

Rewilding forces

For me four trends explain why rewilding is big now.

The first is the comeback of large animals in Europe which is an outcome of strong laws, conservation management and rural depopulation. This has created the perception that even in densely populated Europe humans and large animals can get along.

The second are advances in ecological science and conservation that are unsettling some of the conceptual underpinnings of conservation policy

It has long been realised that the biodiversity of an area is the function of the interactions between composition, connectivity, and ecosystem processes or function.

But it is only in the last 10-15 years that advances in computing have enabled ecology to engage fully with the complexities of the later. For many ecologists, rewilding embodies advances in their science.

But rewilding ideas are also driving ecological science.

In particular, Frans Vera’s argument that that there is a forth European natural archetype – one of grazers and grasslands -challenged ecologists to think about some of the fundamental assumptions underlying their science. Crucially, his theory of cyclic vegetation turn-over attracted the attention of paleo-ecologists.

Vera argues that European culture is based on 3 natural archetypes: high forest, the uplands and the pastoral. He argues there is a forgotten 4th – grasslands & graziers.

Now paleo-ecologists are a learned and authoritative bunch and they made two things clear: 1) there are multiple-past natural states, or natural baselines and 2) ecosystems are always in transition.

Along side these advances in ecology, conservation science has broadened beyond its natural science roots to embrace social and political science.

This new inter-disciplinary conservation science has adopted three important insights: 1) the natures (baselines) we choose to conserve are a cultural decision, 2) we have internalized ecological impoverishment in our culture, policy and institutions, 3) we can’t restore past natures, but we can take inspiration from the past to guide future natures.

Rewilding is big now because rewilding practice and advances in conservation theory are increasingly inter-twined.

However, both are ahead of nature policy

My third explanation for the rise of rewilding is that rewilding visions and practice seems to chime with trends in outdoor recreation. I´m sure we’ve all noticed the growing popularity of mountain biking, wild swimming`, hill running and the like ´- these all suggest a desire for more active and immersive engagements with nature ´ what George Mombiot termed ‘rewilding the self’.

My fourth reason for why rewilding is taking off now is the attitude of aspiring conservation professionals.

Ten years ago our MSc students told us they had little interest in learning about biodiversity loss and back-to-the-wall strategies to protect remnants of past natures. The education they wanted was one that empowered them to develop conceptually rigorous and innovative means to shape a better future for nature and for society.

This shift in aspiration is significant. Twenty years ago my student’s heroes were esteemed scientist such as E.O. Wilson and conservation biologist such as Russ Mittermeier. Eminent and charismatic scientists talking truth to power and framing the biodiversity agenda. Today their hero’s are local, entrepreneurial conservationists – people like the rewilding practitioners I’ve spent the last days with. People who through tenacity, persistence, ingenuity and vision can find ways to work with complexity and restore nature in ways that benefit culture and economy.

So why now? In my view rewilding is gaining profile now because it is given form to wider currents in science and society.

Becoming more than a conservation zeitgeist

There is little doubt in my mind that rewilding is the conservation zeitgeist of the moment. But it is vital that rewilding become more than a fad or enthusiasm. I believe the conservation movement and Europe in the 21st century needs rewilding and here are my three reasons why.

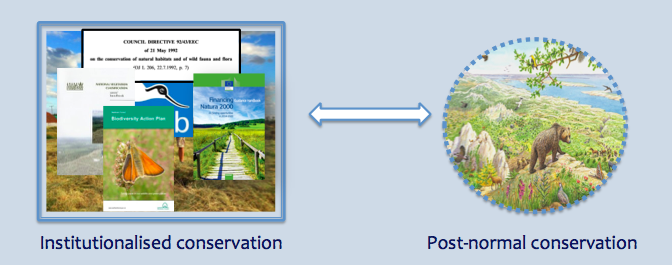

First, our European nature institutions are strong, powerful and have achieved much – but they are ageing. To keep relevant institutions must change, adapt and modernize. However institutions tend to be path dependent and resistant to change.

Institutional theory suggest that one way to modernise institutions is to create ‘post-normal’ ways of doing things outside the institutions: new and innovative approaches that challenge and contrast current practice.

Rewilding is doing just this. It is creating a new body of conservation theory and practice that institutions can reject, appropriate, adapt or adopt. A challenge for rewilding will be to ensure that our work builds its trans-formative potential.

The second reason the conservation movement needs rewilding is because technology looks set to bring about major changes in society.

If you think the internet, smartphones and social media have had an impact, Kevin Kelly in his recent book The Inevitable argues that we haven’t see. anything yet. Multiple artificial intelligence are just kicking in and are likely to change everything. I agree with him, and would add that if conservation is to retain its position as a cultural forces in the 21st century we must engage with the information revolution.

The question is how.

Kelly poses these interesting questions which to me seem relevant to rewilding and conservation futures.

- In a future where everything is streamable, copyable, rentable and plentiful what will be valuable?

2. If, as seems likely, computation replaces 70% of today’s occupations by the end of the century.

“What will we all do? “ “What will be the purpose of humanity”

Kelly’s answer to the first question seems to chime with the new nature-based economy ethos of rewilding Europe. He argues that what will become valuable is experiences and in particular personalized, embodied experiences. Rewilding projects across Europe are beginning to do just this – creating opportunities for people to have very special and tailored wildlife experiences.

Kelly doesn’t offer an answer to his second question but rewilding seems to be doing so.

Freed by automation we could invest our energy and capital in restoring the Earth’s natural systems – in making our planet more livable for all life. This would provide purpose and generate rewarding jobs and lifestyles.

My third reason relates to Brexit.

Every conservationist knows that we need environmental governance at a level above that of the nation state.

Brexit suggests that ordinary citizens are comming to perceive Europe as Brussels – faceless technocrats regulating for economic efficiency with little concern for what matters to them in their everyday lives.

The European project needs to communicate a new vision and I believe that nature and rewidling can play an important role in this.

Iconic landscapes and species have long been deployed as means to generate a sense of collective identity and territory that transcends political structures, class and ethnicity. Think of the role of the US national parks in constructing a sense of what it means to be American. Or the role of UK national park policy in re-imagining what it meant to be British after empire.

I believe the emerging network of European rewilding sites can play a similar role in constructing a new sense of Europeaness

This new map of Europe is fresh, compelling and exciting.

This new map of Europe is fresh, compelling and exciting.

Rewilding is creating new places to know, discuss and visit. Places that generate a sense of hope, pride and maybe awe, places that create a sense of being European.

Investable Earth: an environmental narrative for the 21st century

So to conclude, and bringing these themes together I believe the conservation movement needs rewilding because we need a new overarching environmental narrative fit for the 21st century.

The 1970s narrative of a finite nature that we must protect from the humanity’s wounding ways is increasingly a turn off. The 1990’s narrative of a natural capital and ecosystem appeals to politicians and policy makers but is divisive within our movement.

Rewilding is beginning to frame a new narrative – one of investing in the restoration of natural processes to generate value for all. I think this narrative has widespread appeal and trans-formative potential.

This is why I am proud to be here this evening.