Photo: Paul Jepson

This is the text of a lecture I delivered in the Valuing Nature Keynote lecture series in London on 22 September 2016

—————————————————-

Helen Meach, CEO of Rewilding Britain started a recent article in Ecos with the statement:

“Britain is one of the most ecologically depleted nations on Earth”.

Given the interplay between ecology, landscape and identity I realise that such statements can appear provocative. However I ask that you receive it in the spirit its intended. As an invitation to reassess, revisit and reflect upon our relationship with nature and landscape. This for me is what rewilding represents and signifies.

I’d like to start with an illustration of what ecological depletion means for me.

Photo: Paul Jepson

This summer we holidayed in Slovenia’s Triglav national park. Slovenia has undergone spontaneous rewilding since WWII. Nowadays this landscape supports a huge variety of out door activities enjoyed by people from all backgrounds: multiple types of walking, cycling, swimming and canoeing, skiing in the winter, canyoning, and paragliding, eating out and hanging out.

The hills are alive with the sound of laughter

We hiked into the mountains and alms where the soundscape was one of laughter – groups of friends sharing stories over a radler. It struck me that the natural value they were capturing was conviviality – a state of being we surely all value.

I contrast this European upland experience with our Whitsun hike up Snowden. On the way up I saw five birds – 3 meadow pipits and 2 stonechats. My daughter didn’t find any flowers worth photographing and when we reached the summit I overheard a Dad explaining that the herring gulls scrounging scraps weren’t “mountain birds, they shouldn’t be here. The raven is a mountain bird”.

Photo: Paul Jepson

I share these recollections to make two points.

The first concerns where natural value resides.

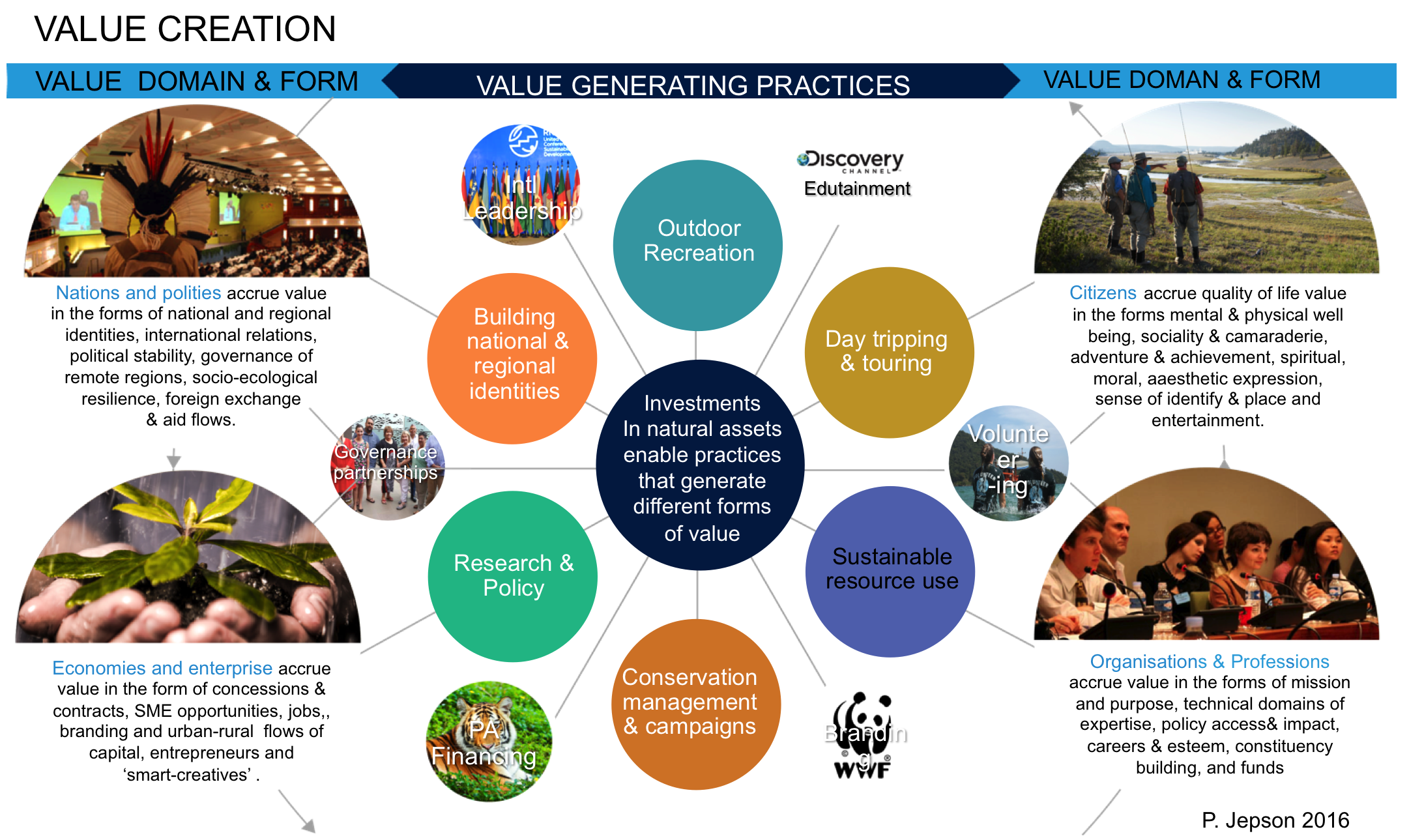

I think of value as a relational outcome – as an emergent property of interactions between entities and systems. It follows that natural value is generated through ‘practices of engagement’ – that range from the informal to the mechanised.

In relation to practices of commerce, value long ago became standardised as money. However, in other areas of life this has not been the case – relational values are values that contribute to a good quality of life and social well-being. They are expressed in social values such as tolerance, democracy and in the conservation values that govern our relations with nature e.g. the moral imperative to avoid the extinction of species and the idea that monuments of nature are part of cultural heritage.

If systems are simplified there are fewer entities to interact – function and process is depleted – and the value (service) generating opportunities of our ecosystems are diminished or constrained.

This is the situation we are in now.

This concept that value is an emergent property of interactions between entities and systems also applies to the concepts of ecosystem function and services.

Restoration of trophic levels creates rich and dynamic systems with numerous niches that allow species to flourish and create a diversity and abundance able to support a range of value-generating practices

The second point I want to make is that as a society we seem to have internalised ecological impoverishment in our culture, policy and institutions.

Maybe some of you like I spent teenage years listening to Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon”. My problem – as an ecologists and geographer – is that when I visit our uplands I can’t get that Roger Waters lyric out of my head “hanging on in quite desperation is the English way”.

This annoys me but pushes me to ask why? Why is it that we have come to value bleakness and become overly protective of our wildlife?

We know that there was a major shift in practices of engaging with nature between and after the two world wars. Up until then hunting, natural history collecting, bird-keeping, the harvesting & eating of natural produce were all mass participation pastimes. But due to the impacts of industrialisation – in it’s various guises – our ecosystems became steadily less able to sustain such practices and this was becoming clear to scientists.

Rewilding the self. Photo: Colin/Chillswim

And then we had men coming back from the hell of warfare and sick of killing. The stories they could tell to their families were not of the horrors they’d experienced, but of the symbols of hope – the swallows nesting in the trenches and skylarks singing above the battle field.

The new discipline of ecology argued for protection of the remnants of what we had left and public opinion supported this – it no longer seemed right to hunt, collect or harm wildlife.

But that was three generations ago. It is part of our cultural heritage but I believe people want to move on – they want better quality ecosystems that restore the opportunity for the rich and diverse engagements with nature that contribute to a quality life, and that contribute to a new and better society.

This for me is where rewilding comes in.

So what is rewilding?

I’d first like to address two common perceptions.

Rewilding is about abandoning land.

Abandon to me means discard or turn your back on something. I hope my remarks on relational value will have made it clear that rewilding is about restoring ecosystems to revitalise practices of engaging with nature and landscape. For me it is about reformulating old and creating new connections.

2. Rewilding is about reintroducing the wolf.

The media loves this idea but it is a very minor aspect of the rewilding discussion in the UK and Europe. Of course this is not the case in areas of the US such as the Yellowstone ecosystem.

I am also aware that the term (Re)(wild)ing puts some peoples backs up. For instance in Scotland the legacy of the clearings has generated sensitivity to agendas that appear retrospective and frame the highlands as an unpopulated wilderness.

For me rewilding is a label like punk or hippy that that signifies an unsettling – a desire and a need to shake-up the present and move forward. I see it as an ‘opening’ – a space of creative thinking and action on future natures. Where our multi-cultural society can outline and debate new visions for society-nature-landscape interactions.

Rewilding is also consistent with the general direction of travel in ecological science and environmental policy. Three components of ecosystems interact to determine the natural value of an area: composition, structure and function. Historically we have given most attention to composition – in part because it converts into strong law and measurable targets.

The Lawton report “Making space for nature” foregrounded the need to move on with its “bigger, better, more connected” strapline and rewilding is a progressive expression of this call.

Earlier this year Frans Schepers of Rewilding Europe and I published a policy brief titled “Making space for rewilding” where we outlined 7 emerging rewilding principles following discussion with rewilding experts and EC conservation lobbyists. I’d now like to run through these.

The first is restoring natural processes and ecological dynamics: abiotic, biotic and/or socio-ecological. This is the core of the emerging rewilding movement.

Second is the bigger picture aspiration of creating self-sustaining, resilient ecosystems at the scale of landscapes and regions. It is useful to note that rewilding has emerged following the accession of east European countries to the EU. This accelerated rural depopulation and declines in livestock grazing affecting the region’s herb-rich grasslands. Conserving these habitats with agro-environment schemes designed for the western European situation is impractical.

Third is taking inspiration from the past but not replicating it. This is a key contribution from long-term ecology and environmental politics. Ecosystems have moved on and their are multiple past ‘natural’ baselines. Choosing one baseline to restore to would be political and likely impossible to achieve anyway.

Forth is working towards the ideal of passive management where, once restored, we step back and allow natural processes to shape conservation outcomes. The idea of self-wilded lands in central to rewilding but this principle recognises that many ecosystems are so degraded that in many cases management activities will be necessary in order to ‘kick-start’ ecosystem processes

The fifth principle relates to the above and is a situated approach where the goal is to move up a scale of wildness within the constraints of what is possible. Rewilding is not just something for remote and large natural areas: giving ecosystems an upgrade is something to aspire to everywhere.

Sixth is creating new natural assets that connect with modern economy & society. This reflects the perception that rewilded landscapes are cool and exciting for many urban people and this can form the basis of new or extended recreation economies in rural areas. It is also a reflection of the influence of the 1990s livelihoods agenda in conservation and the entrepreneurial attitudes among many modern conservation professionals.

Lastly, is the principle of reconnecting policy with public conservation sentiment. I’m not sure this is really a principle. Many of us active in rewilding feel we are just part of a zeitgeist, but at the same time we also want to articulate fresh conservation visions that will engage and inspire citizens.

Time to walk the talk

The question now is how to proceed– how can we put rewilding into practice beyond a few model sites or places.

This time last year I was thinking about the feasibility of experimental rewilding sites on ex-mining landscapes with high ‘green space’ value but lower ecological and agricultural value and the idea of a competitive scheme – based on the successful new national forest model of the 1990s.

I think there are many other places with great potential for ‘demonstration’ rewilding projects. I drove past one recently – the Hole of Horcum shown in the header image – imagine a landscape evoking the Ngorongoro crater in Yorkshire! I think such a place might give a boost to the upland economy of the North York Moors!

Brexit means CAPexit

But June 23 opened a new dynamic that I’d like to explore in the remainder of the talk

Keeping CAP as it is can hardly constitute the break from Europe that the majority of landowners and farmers voted for. The means we have to decide what to replace it with

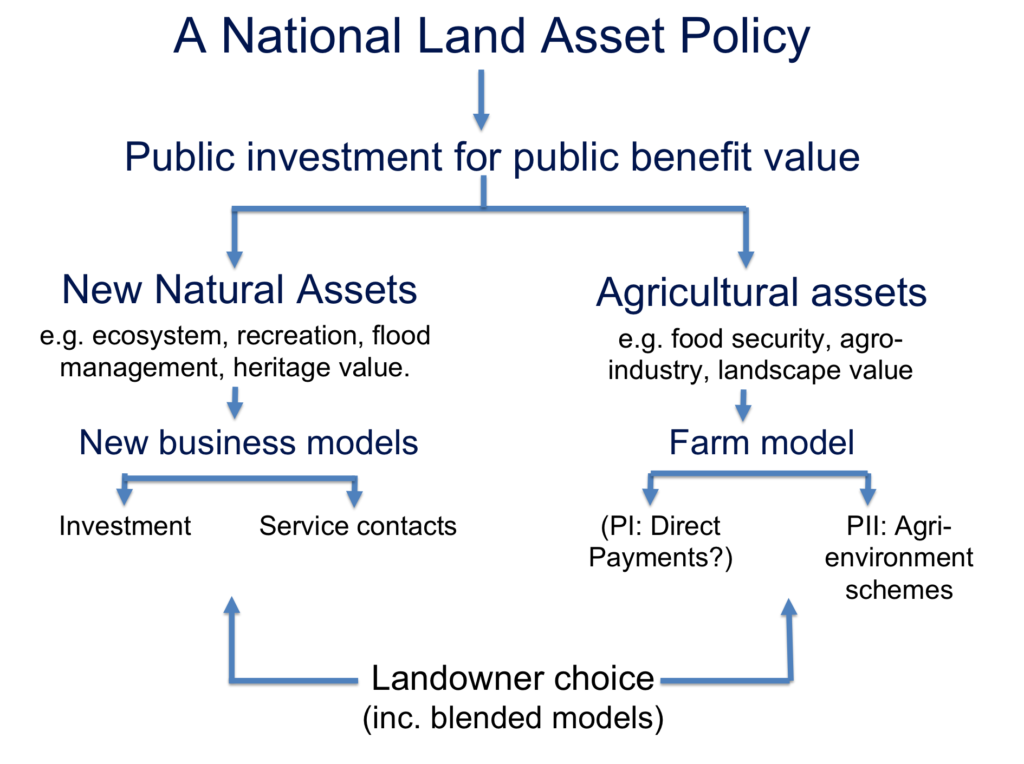

My rewilding-inspired suggestion is that we replace it with a national land asset policy that offers landowners choice on whether they want to develop and manage agricultural assets or natural assets or a blend of the two.

(c) Paul Jepson

Now if you will bear with me I’ll introduce some of the conceptual underpinnings of this idea.

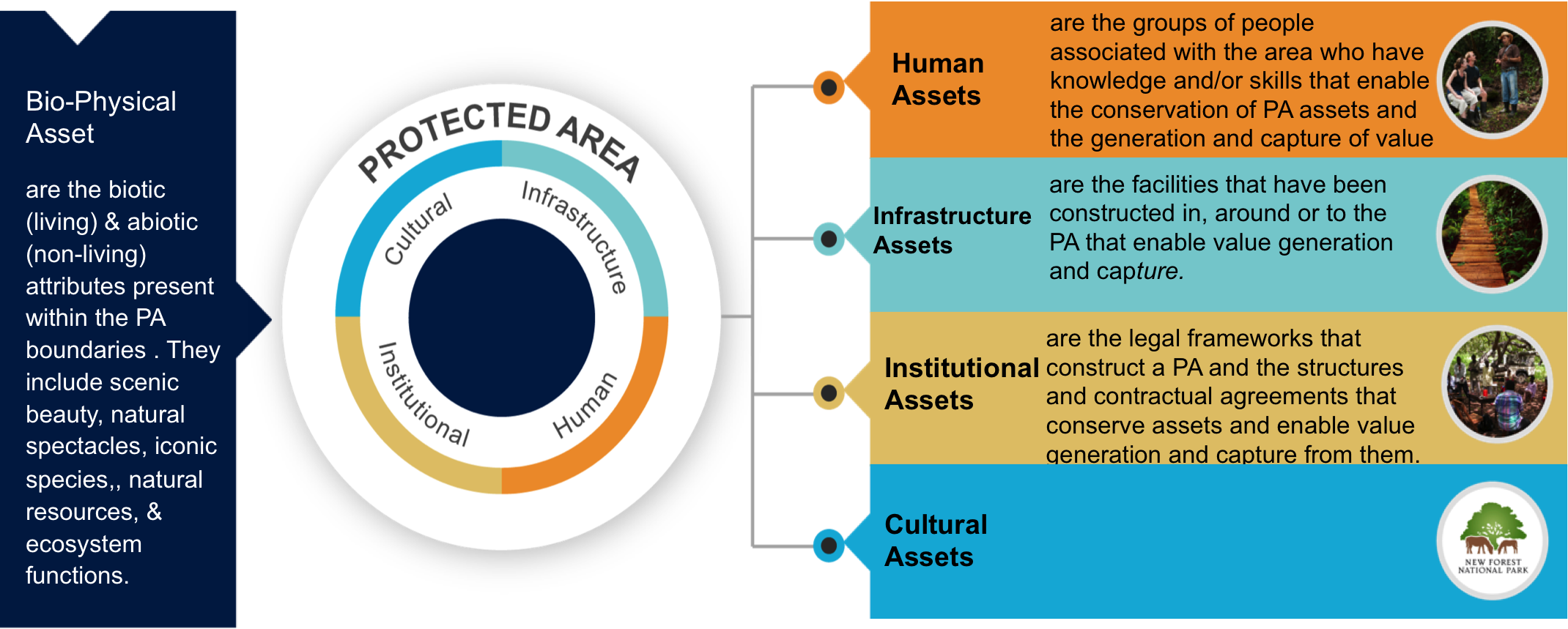

The natural capital frame represents a welcome engagement of economist in natural resource policy. However economists often view capital and asset as interchangeable terms. Dieter Helm defines natural capital as the assets nature provides us with for free: geology, water, life and frames these natural assets as key inputs to the economy. They undoubtedly are but this concept of natural assets is limiting and becoming ever more divisive among ecologists – perhaps because the notion of natural capital aligns with the ills of capitalism and growing concerns with neo-liberal agenda.

In my view natural assets are not provided by nature, rather they are produced by human cultural engagements with the bio-physical world. I understand assets as a more expansive concept that includes forms of capital but refers to things that can generate forms of value beyond what can be monetised.

Think of your home or our planet. Viewing the Earth as capital seems wrong. But as an asset? I can live with that!

Together with colleagues at the Smith School and the University of Alagoas in Brazil, I have been working up the idea of natural assets to restate the policy case for protected areas in ways that might be more meaningful to politicians, policy makes and the wider public.

I suggest that our asset framework could be adapted to the concept of land assets.

It is core is the idea that a nature reserve or a land parcel is made up of a package of five asset types that interact to generate forms of value.

The character or state of these assets and their interaction determines what value is generated and who can ‘capture value’ from these assets.

My point is that practices of engaging with nature generate multiple forms of value and a national land asset portfolio that supports multiple practices of engagement generates more overall value to society.

So to summarise

Rewilding signifies a desire for the restoration of functional ecosystems & the creation of new natural assets better able to generate life-quality values

Practices of engaging with nature generate value and a land asset portfolio that supports multiple practices of engagement generates more overall value to society.

Replacing CAP with a Land Asset Policy that invests in new natural assets as well as agricultural assets would empower landowners & rural communities to develop new rural economies.

Rewilding principles amount to a distinct and complimentary approach to biodiversity and landscape conservation – one that is about investing in new natural assets and that can be adapted to local context.

If we can agree a fundamental logic of what our land is for we all have a bright future.

Thank you for listening.

Paul, I like your thinking when brave creativity is sorely required at an uncertain time. But as mentioned to Rewilding Britain and as John Lawton mentioned to me years ago, we must seek to take as much of society with us, rather than drive idealist principles through with high handed views that certain ecosystem services are defunct in today’s society.

I refer to some rewilding disciples http://www.charteredforesters.org/opinion/item/284-rob-yorke-on-george-monbiot-rewilding/ who seek to drive a wedge into landowning interests, including some cultural practices such as shooting, that may in fact be more natural allies to elements of rewilding, than alternative land uses of agriculture and commercial forestry.

My journeys through northern Romania were a little more raw than yours. Helping the locals scythe grass on steep meadows was more a sweaty, alcohol-addiction ‘grunt’ job. Conversations with others on the co-existence of transhumance shepherding with wolves dwelt on them being hunted when they became a problem; that was the natural ‘wild’ order of interactions that we risk failing to understand in wanting more unfettered wild here (I agree the wolf is a media diversion but same applies to keystone species from beaver to boar – let’s have them but let’s hunt them when required).

I’m lucky to have the wild stuff here in the hills http://robyorke.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/ECOS.whole_.pdf and agree Paul that more natural led processes would work in some areas – count me in but allow me to be your ‘critical friend’ in cultivating those that can deliver resilient public benefits – not just shouty punk public opinions!

Best, Rob

Rob, the rewilding issue has attracted voices who engage in a confrontational political style but there is also a growing group of thinkers from all backgrounds who are engaged in considered, reflexive and open discussion about nature conservation – and by extension landscape futures. I am part of the latter group. Your framing of me as a shouty punk, pressing idealistic principles on others, who has only known comfortable engagements with rural lives is a bit of a laugh when we’ve only ever met for 10 mins!

I believe in academic openness and public discourse and as part of this get out and do talks and engage in online media. However, as we all know it too easy to post knee jerk negative and personalised commentary on social media. Many people find this intimidating, unpleasant and disingenuous and this can close down important voices in discussions.

There are two things I’d be interested to hear your perspective on. 1) what do you think about my suggestion for a national land asset policy to replace CAP? 2) I’m meeting young farmers at rewilding meetings who are talking about mechanised loneliness and depression in the countryside and who are looking for ideas to shape a new and better future on the land. To what extent is this part of the rural narrative that you seek to represent?

Best regards Paul