In the last 30 years Brazil has significantly expanded its network of protected areas (PAs) : nowadays over 17% of terrestrial land and inland waters and 1.5% of coastal and marine areas are protected.

The Brazilian protected area system is the largest in the world. Brazil is recognised internationally for its leadership in biodiversity conservation and the major contributions it has made to the meeting of targets agreed under the Convention on Biological Diversity. However, these achievements are coming under threat from economic development interests.

In these hard economic times, with a 2015 budget deficit of R$613 billion or 10.4% of GDP, some are beginning to question the value of reserving so much land for conservation. Might the needs of the nation be better served by de-listing some reserves and making the land available for other land uses such as agriculture and mining that generate significant economic, tax and employment value?

It is important that conservationists make the case for protected areas in ways that a meaningful to politicians, policy makers, entrepreneurs and citizens. Given that 85% of Brazil’s 206 million citizens live in urban areas it is important that they also see the value of protected areas in order to assure democratic support for PA policy.

Since the late 1980s the two main arguments for creating protected areas have been the preservation of biodiversity and protection of local (e.g. rubber tapper movement) and traditional ways of living. These arguments are important and powerful, but biodiversity arguments are highly technocratic and protecting traditional forest-base livelihoods may have little relevance to the lives of urban people.

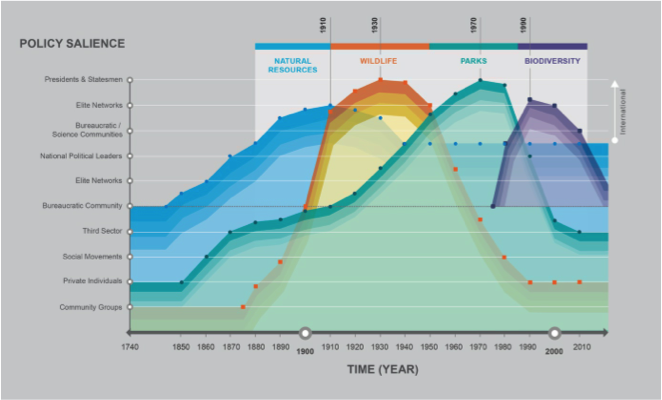

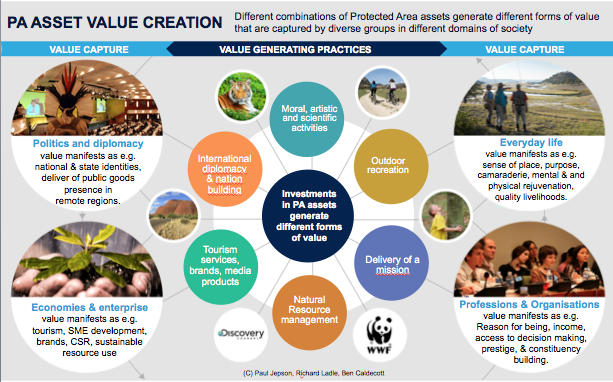

We have developed a new framework that communicates the multiple forms of value that PAs are, or could generate, and the domains of society where this value is, or could be, captured. Our framework draws on policy histories of protected areas from around the world to capture the various value-generating purposes that have motivated the establishment of PAs over time. We have been testing and developing our ideas in Brazil.

The goal of the 1st ‘wave’ was to protect natural resources to assure long-term supply of goods and services. The 2nd was driven by the moral imperative to avoid the extinction of wildlife and assure the value it generated for culture and public enjoyment. The focus of the 3rd wave was outdoor recreation and vacationing and the value this generates for the health and well-being of urban citizens and national pride. The imperative of the 4th wave is to conserve biodiversity for its own sake and as a resource for local livelihoods: it has been a major influence on Brazil PA policy

The asset framework is intended as an aid to strategic planning, communication, and decision making relating to protected areas policy and to support the case for continued and new investment in PAs. At the core of the framework is the concept of ‘asset’. The term asset is widely used in economics and finance and in everyday language of English-speaking countries. Portuguese lacks a commonly used equivalent: the closest word is patrimony, which refers to property and heritage passed down from ancestors. An asset is something – land, investments, attributes – that can generate value. This maybe financial (cash) value, but many assets generate forms of value that cannot easily be transferred into money.

Photo: Reinhard Jahn, Mannnnnheim. Wikimedia commons

For example, land is clearly a type of asset. The falls at Iguazu are a special natural asset. Through investments in visitor infrastructure (e.g. vistior centres, walkways) and institutional assets (e.g. World Heritage Site and National Park designations) the park now returns sustained and varied value. It generates monetary value for the municipality and the tourism economy, but the millions of visitors and the nation as a whole capture forms of value that are difficult to convert to money such as the thrill of experiencing a natural wonder or a sense of national pride.

Drawing on these logics our framework views PAs as land assets, a special type of real estate asset class with natural characteristics that can be managed to generate long term value for society and the natural world.

Our asset framework has three components: i) protected area assets; ii) the forms of value generated by these assets, and iii) the domains of society where beneficiaries capture (or have the potential to capture) value from PA assets.

Protected area assets are divided into five broad categories, each of which can be further divided into sub-categories.

Biophysical assets are the biotic and abiotic attributes present within the boundaries of the PA. Examples are scenic beauty, natural spectacles, iconic species, and natural resources such as timber.

Human Assets are groups of people associated with the PA who have knowledge and/or skills that enable the conservation of PA assets and the generation and capture of value from these assets. Examples include: PA technical staff, rangers, guides and traditional peoples.

Infrastructure Assets are the facilities that have been constructed in, around or to the PA that enable value generation and capture. They include transport, management & visitor infrastructure, public utilities and historic buildings or features.

Institutional assets are the legal frameworks that construct a PA and the structures and contractual agreements that conserve assets and enable value generation and capture from them. They include Conservation designations, decision making structures, partnership/ commercial agreements.

Cultural Assets refer to the interactions between the PA and wider cultural practices and narratives that create a public identity for the PA. They include things like brands and emblems, creative interpretations, cultural events and myths & legends associated with the PA.

The specific combination of assets located in a PA will vary in relation to bioregion, country, the era of establishment and the management function and history of the PA. Further, the interactions between different PA assets will generate different combinations of value that can be captured by different groups in different domains of society.

The framework identifies four main domains of society where PA value is generated and can be captured. These are the domains of 1) everyday living, 2) politics and diplomacy, 3) professional and organisational life; and 4) economy & enterprise.

Practices in each of these domains of life interact with PAs to generate forms of value for the person, group or entity involved. So for example citizens capture life-quality values from biophysical assets such as scenic beauty, iconic species and remote landscapes in the form of aesthetic appreciation, treasured memories and adventure. Such value emerges from practices of day-tripping, trekking, watching wildlife documentaries and the like. Political leaders capture diplomatic value through demonstrating leadership in an important area of international policy and mobilizing PA asset to generate a collective sense of pride and identity at the national or state level.

Our framework enables four question to be asked: 1) What forms of value are PA assets are currently generating and for whom? 2) What forms of value are wanted and who decides? 3) What forms of investments are needed so intended ‘publics’ can capture investment value? 4) What forms of value could be generated from PA assets and for whom?

These questions recognise the important dynamic that exists between those who set PA policy and those who can capture the forms of value that PA asset create. Answering these questions has the potential to restate and refresh the policy case for PAs and enhance innovation, transparency and democratic accountably in PA policy and attract new investment.

During April we toured PAs in Rio State to ‘ground’ this thinking. The following three posts illustrate the perspectives and ideas prompted by the application of this asset approach.

Investing in Tamarin landscapes: an asset-based vision

Tres Picos State Park: utilizing transport infrastructure assets to generate value

We are also applying the framework to over 200 management plans to refine the typologies and ask what biophysical assets are considered important and who or what captures value from investments in these assets. A longer and more technical account of the asset framework, including a Brazil case study, is available here.

We welcome comments and reactions.

Our research is funded by Brazil CNPq-PVE Grant#400325/2014-4